"Hand of dead man writes"

"These things it’s likely may seem Minute and Trivial, but without ‘em great Things cannot subsist."

Remember when I said this letter about commonplace books was going to show up in 4 weekly installments? Hilarious, right? Turns out I can only write term papers, not 500-word weekly response posts. But joke’s on you, you signed up to read them. Take your time. I’ll see you again in October.

1. “strange preparations… consequences”

Enough waiting around. Let’s crack open some notebooks, shall we?

I mean, come on. Frida Kahlo’s commonplace book was always going to be cooler than yours or mine, right?

But they don’t all look the same. People have different interests and preoccupations. For example, Lewis Carroll was interested in designing mazes.

This image is from a blog post at the Harry Ransom Center, who hold his photograph albums, but haven’t yet digitized his commonplace book, as far as I can tell. For more sketches and notes, try the Bodleian’s digital collections.

You’ll recall from last time that H.P. Lovecraft’s commonplace book — or at least the digitized version we have access to thanks to the good folks at Brown — was a bunch of cramped, compressed typescript pages. It’s not Lovecraft’s raw scribblings, it’s the story idea notes he (or his secretary) thought were cool enough to type up as examples of his thought process and send to the publishers, so it’s already been through an editorial process of sorts. Lord knows what the discard pile looked like.

Another Internet favorite is the journals of Octavia Butler, held at the Huntington Library.

You can find these pages of her notes to self all over the Internet, without precise citations, but the Huntington hasn’t yet made them available digitally as far as I can tell, which means that these images come from blog posts around the 2017 exhibition. So they’ve also been through a kind of editorial process-as-popularity contest, where the Internet took what it liked and ran with it. More on that later.

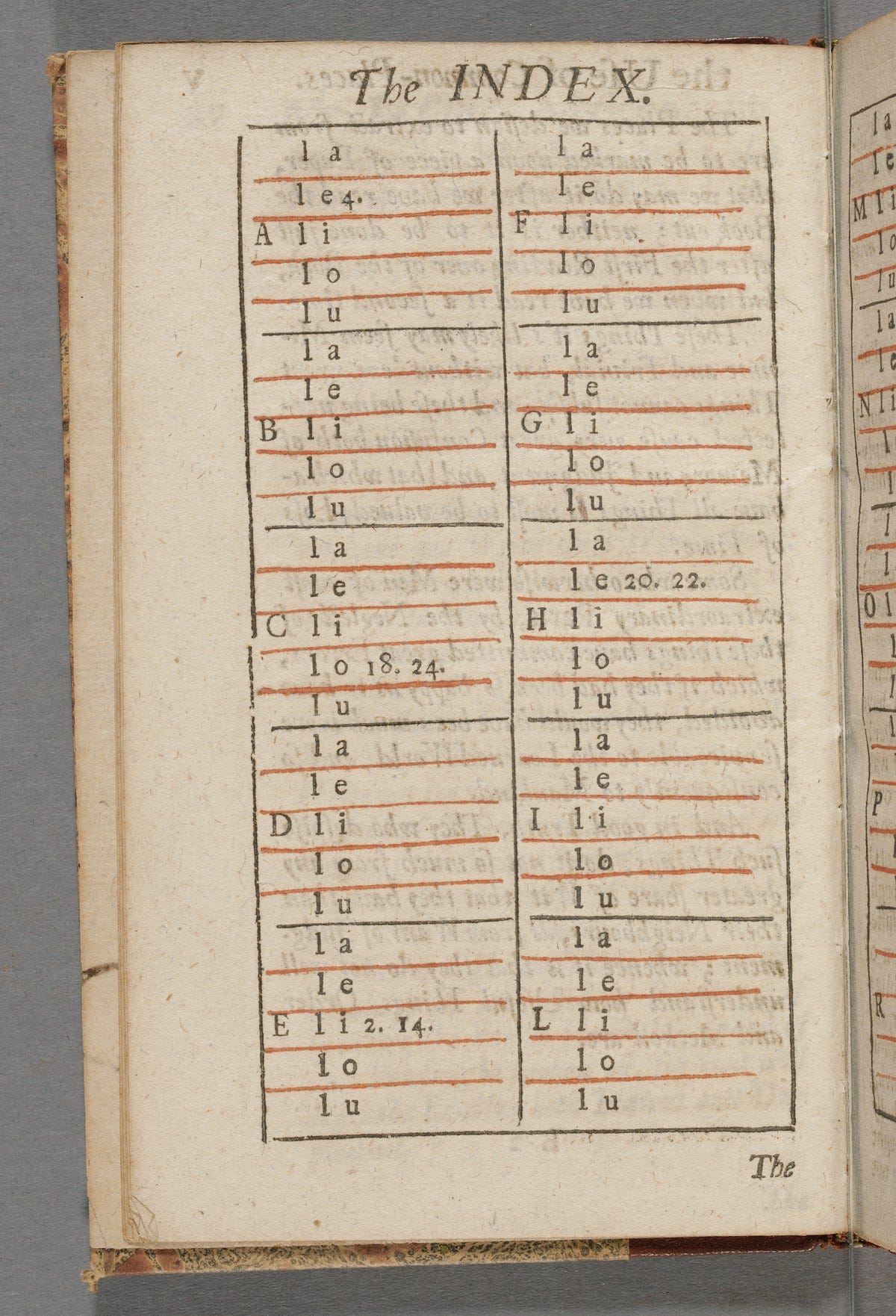

Let’s take a gander at John Locke, whose most interesting contribution, to me, isn’t his own commonplace book, but his instructions on how to create one. Here’s his exemplar index page, printed in A new method of making common-place-books (1706):

That is one organized dude. If any of you have ever tried bullet journaling before, that might look familiar.

Finally, here’s Elizabeth Cady Stanton, from the Boston Public Library via the Internet Archive:

Her bolded section reads, “Thus there exists [sic] no opinions, however rigorous, but what find evasions — no minds, however pacific, but kindle in great political convulsions,” quoting Book V of the History of the war of independence of the United States of America by Charles Botta. Hardcore.

Clearly, the commonplace book is a wide-ranging genre. It’s about taking things from your environment and saving them for later, and there are as many ways to do that as there are people doing it.

You can see above that many of these are not just books with quotations, but also sketchbooks, journals, notebooks, dream journals. This open format has led many writers and thinkers today to consider a great deal of things to be modern analogues to commonplace books, from Google search results to Pinterest to e-books to Tumblr.

I argued last time that commonplace books are portraits of a person’s intellectual life, of the quotes and sayings they find interesting, informative, instructive. But that’s kind of an anachronism, because for many who kept commonplace books, developing the internal creative life wasn’t always the goal.

2. “hideous old book discovered with directions for shocking evocation”

“It is an Old Saying, That that is the Truest Poverty, when if you have Occasion for any Thing, you can’t use it, because you know not where ’tis laid.”

That’s from the introduction to John Locke’s A new method of making common-place-books (page ii), (same book the scary index above comes from, and the subtitle to the newsletter itself.) It’s attributed to Columella, an ancient Roman writer, but it applies to basically anyone trying to collect their thoughts and citations in the age before Google.

Locke’s commonplacing method came from the desire to be able to find exactly what he needed to know, when he needed it. Marshaling useful quotations into strict order was the only way to build and develop a body of knowledge that could then be drawn from and used to pursue further lines of inquiry.

“I take a White Paper Book of what Size I think fit, I divide the Two First Pages which face one another, by parallel Lines, into Five and Twenty equal parts, with Black Lead; after that, I cut them perpendicularly by other Lines, which I draw from the Top of the Page to the Bottom, as you may see in the Table or Index, which I have put before this Writing. Afterwards I mark with Ink every Fifth Line of the Twenty Five that I just now spoke of.”” (A new method, 4)

This kind of intensive index instruction makes sense in the time before computers. You have to be able to find the things you want, and developing systematic ways of doing so helps you build on your knowledge more efficiently.

Commonplace books were written by hand, as though the very act of taking down someone else’s words by hand could imbue you with some of their genius. “Hand of dead man writes” is one of those creepy H.P. Lovecraft story ideas I showed you last time. (As are the rest of the section headings. I couldn’t resist.) But it’s also a pretty apt metaphor (from a racist old man) for the above school of thought.

This is the Great Men of History theory of commonplace books, that they exist primarily as aides-memoires to help people (read: white men of means) take in the wisdom of previous Great Men in order to become Great Men themselves that will be quoted, in future, by new Great Men.

People often get worked up about the physical ways we take in information and their relative moral value. Listening to audiobooks isn’t real reading, e-mails aren’t as serious as letters, text messages are more callous than phone calls. And listen, the social value of all of those different things is certainly real. The effort it takes to handwrite notes on a notecard is much different to copy/pasting vast chunks of text from an online article with the tap of a key. The physical ways we ingest information change how we process and integrate that information.

I, personally, cannot imagine being expected to remember anything without being able to look it up almost immediately online, much less having to remember important quotes from useful books I’ve read over the course of my entire education.

Many people might consider this a mental failing and evidence of the erosion of our ability to cogitate due to the vices of our modern era, like some kind of Idiocracy-themed Black Mirror episode.

Those people might be interested to hear about previous similar handwringing over newly available print and paper, and how the act of writing notes means you no longer need to be able to call forth your university lecturer’s entire 3-hour oration on the tripartite nature of God, from memory, which betides a woefvl erosion of ovr abilitie to cogitate dve to ye vyces of ovr moderne era. Anyway,

Not being able to Google seems like a pretty understandable reason for dividing your thoughts and life into tiny little boxes. But what’s interesting is that those are very similar instructions to the how-to page of the Bullet Journal website, a somewhat popular daily scheduling system that’s been taking over internet productivity spaces for years.

Bullet Journaling is all about making your life easier by, first, making it harder so that you leave behind everything you don’t really, truly need. It’s about working against your natural inclinations on the way to enlightenment, or at least mindfulness.

Both Locke and the Bullet Journal people want you to write everything down systematically, in a way contrary to your natural inclinations. No more scraps of paper getting lost in piles, or half-remembered thoughts. If you can organize and shift your scheduling and to-do lists into this way of doing things, the thought is, you can finally be your most productive self. But for Locke, it was an organizational necessity. For Bullet Journalers, it’s almost a ritual.

We don’t need Locke’s rigorous handwritten index methods anymore. That’s what fancy note-taking apps are for. So why bother?

3. “man followed by invisible thing”

People were commonplacing long before Locke wrote his guide. Atlas Obscura has a fun introductory article about zibaldones, 14th-century diaries by middle-class people in Venice who recorded the goings-on of their everyday lives, with drawings, songs, prayers, recipes, and more. (Apparently in Italian “zibaldone” means “a bunch of stuff”.)

Commonplace books are also, and have always been, a kind of creative scrapbook or journal that is less about the author and more about the author’s thoughts, obsessions, doodles, half-finished thoughts.

People are still interested in making commonplace books now, mostly as lifehacks. According to the New York Times, you should download a bunch of expensive apps (on an immediately-post-grad-school budget they are, guys), link your Apple and Google profiles to all of them, say a little prayer to the god of passwords, and then “digitize” it all by letting Google OCR through a bunch of pictures of your handwritten notes to yourself.

According to Richard Meadows, who writes this pizza-themed money blog (god bless the Internet), “imposing a rigid hierarchy is unnatural!” You should naturally let your thoughts flow wherever they flow, and keep everything jumbled together to promote flashes of inspiration.

For those of you with a literary background, this could all sound a little Enlightenment Rationality vs. Romantic Emotionalism. And it’s not NOT that. But I’m more interested in what the “good” is that we’re meant to get out of all of this natural and unnatural effort. What’s the use?

I mean, “commonplace book” is clearly an umbrella term for various somethings that are at their core quite different from each other, but just because those somethings are different in execution doesn’t mean they’re different in their goals. The Romantic Road and the Enlightenment Road are both intended to get you to your goal faster, whatever that goal is. And the goal seems to be productivity, in both cases.

I can’t be the only person who’s tried to start a workout routine and been stymied by wondering when to eat, protein or carb, how soon before, and then do we do weights or cardio first, and is it the right time of day, or do I wait until later, and should I be fasting intermittently, or drinking coffee beforehand, and did the bagel I just ate erase my half hour on the elliptical, and should I have just done a bunch of jumping jacks instead for 10 minutes as a high-intensity interval circuit? Does jumping out the window count as a high-intensity interval circuit?

Even the Bullet Journal tries to apologize for productivity culture: “The Bullet Journal method is a mindfulness practice disguised as a productivity system. Once you're comfortable with the system above, you'll be ready to move on to the mindfulness practice, and learn how to live with intention.”

I mean, barf, right? What does “living with intention” mean, if not maximizing your every moment in order to get the most out of yourself - the deepest yoga pose, the most restful meditation, the cleanest meals, the highest intensity intervals?

What I’m trying to get at is that productivity is currently how we prove our value to our society (with a little bit of Beauty Culture thrown in there. Don’t even get me started.) Often we’re encouraged to see productivity as the highest good. In other eras, that highest good might have been piety, or sensibility (in the archaic sense: being sensitive to your own feelings and the feelings of others.) It might have been chastity, or rationality, or Stoicism.

This is why the Great Man theory of commonplace books is compelling to some. If we could just marshal our thoughts into orderly lines like Locke taught us, like Winston Churchill learned to do at school, like Marcus Aurelius did (apparently his Meditations, a kind of proto-commonplace, is Bill Clinton’s favorite book. Make of that what you will), then we could all be Great Men, Millionaires, #girlbosses, if only we were Productive Enough.

It can be hard to see the societal narratives we’re living through as we live through them. For example, back in Puritan times, everyone was waiting for their Moment of Personal Revelation from God. They believed it would happen just like most of us now have been raised to wait for the Moment we Fall in True Love at First Sight. It’ll just hit us one day, like a lightning flash, right? Suddenly You Knew He Was The One (where He, in this case, is a particularly angry Divine Presence.) It really reframes all of those early modern conversion narratives - they’re all just describing their meet-cutes with God.

My point is, was John Locke trying to be productive? Were the theologians and great thinkers of the Renaissance trying to be productive? Were the Romantics trying to be productive? Reducing the goal of a commonplace book to productivity, creative or otherwise, reduces our understanding of why they were created and what use we can take from them now.

I’m not saying don’t work hard. I’m saying pay attention to what you’re working on, and working towards.

There’s a reason that I teased this topic in August as “building the cabinet of curiosities”. Commonplace books aren’t just self-portraits, or self-directed syllabi. When we choose what to include, what feeds us, what we think is worthy of our time, we’re choosing from a limited menu. Commonplace books are also portraits of what we’re encouraged to think is important by the society we live in. (That’s right, it’s Society, Capital S. Ooga-booga fingers.) You can only pick and choose from what’s available to you.

And that’s what we’ll be getting into… next time.

I’m loving this series and recently had a conversation about bullet journaling which I thought we had collectively left behind. Guess not.

Personally I probably need a commonplace book for all my commonplaces. I’ve got serious commitment issues and cannot make a full conversion to digital notes & calendars or live without them.

What does your commonplace book look like?