"fisherman casts his net into the sea by moonlight - what he finds"

the more you look, the more you see

Last time, on Commonplace Books Of Our Lives…

…we talked about commonplacing as a technique for organizing thoughts — whether “unnaturally” in regimented order, or “naturally” in a kind of organized chaos that allows disparate ideas to knock against each other, and hopefully inspire new ones.

Ordering your thoughts like John Locke might be helpful if, like John Locke, you don’t have access to easy automated filing systems or the wonder of the Internet. Or it could be useful if, as a devout bullet journaler, you’re attempting to put your thoughts through an American Ninja Warrior-style gauntlet to prove that they’re worthy of taking along with you into next month. On the other hand, organized chaos might be useful if you’re trying to sneak-attack your brain into a new kind of creativity. Either way, both of these ideas are about maximizing your productivity, one of the central virtues of our present moment.

The idea of having to set myself a task to compile a Big List of the Good and Smart Things I Think About Bigly and Smartly in an Important Way, as an Intellectual, is IMMEDIATELY exhausting to me. It makes me want to go eat a bag of Cheetos and watch the Real Housewives of Wherever, or that F1 documentary show which is just the Real Housewives of Cars. Please, god, anything but this.

This is why I’m on Tumblr.

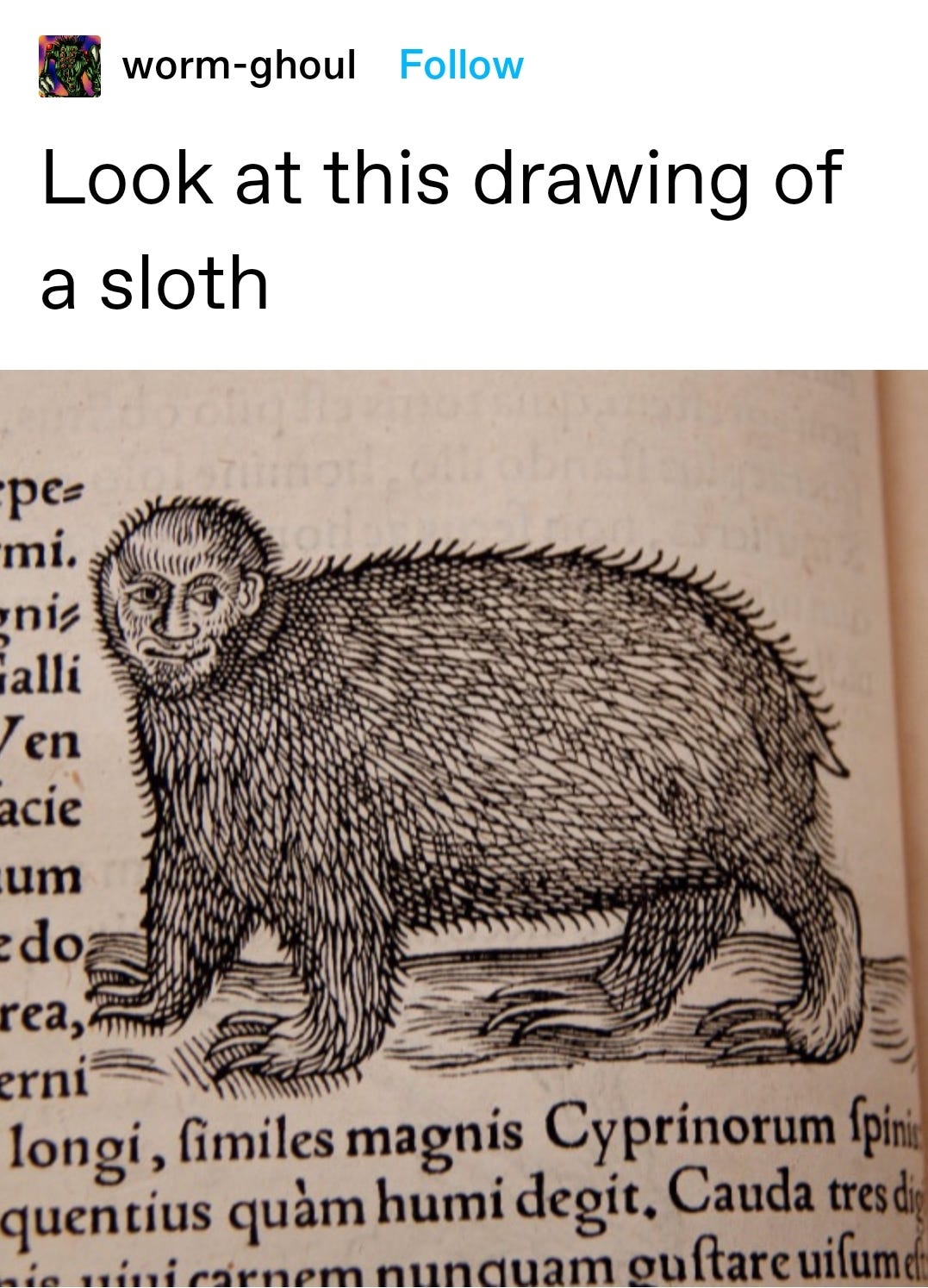

I mean, Get a Load of This Guy:

He seems fun. This is the kind of thing that gets hundreds of thousands of likes on Tumblr.

(Eagle-eyed readers will recognize this handsome devil from Conrad Gessner’s Historia Animalium, which you can peruse at your leisure at the Biodiversity Heritage Library.)

If I’ve learned anything so far this month, it’s that people love to compare commonplace books to social media. It’s a version of creativity-as-curation that people nowadays often understand through comparisons to social media, whether it be Pinterest, Tumblr, or the dearly departed Google Reader.

The argument goes that commonplace books were the internet of their day, ways to create connections between disparate concepts and to mull over half-baked ideas, much like blogs (or this newsletter.)

Shaj Mathew at The Millions argues that commonplace books aren’t like Tumblr at all, because commonplace books are FOR something and Tumblr is, proudly, for nothing. Commonplaces are aide-memoires, Tumblrs are about the #vibes.

But as we’ve seen above, commonplace books don’t have to be about anything, necessarily. (We don’t all have to be John Locke.) One of my favorite commonplace books is David Sedaris’s journals, which he published in 2017 as Theft By Finding.

He describes them as journals, but many of those journal entries consist of real-life conversations and interactions that happen around him. For example, from this excerpt in the Guardian:

At around five, I took the L home. A woman near me had a three-year-old child on her lap, a girl, who looked at me and said, “Mommy, I hate that man.”

What a spectacular thing to record. He transcribes and quotes the words and conversations of the strangers that pass through his life, which to me is not really so different from quoting from books or songs. A phrase strikes you, you take it down. Mommy, I hate that man.

And, as we think about whether commonplace books have been replaced by social media, this kind of free-and-easy recording is the real advantage of the digital age. We no longer have to worry about writing everything we like down by hand. Things CAN just be vaguely or potentially interesting. You don’t necessarily have to be precious about space or about how tired your hand gets copying down the words of Great Geniuses Past. All it takes to grab something shiny from the internet is a couple of taps.

Where are we gathering these shiny objects, like the magpies that we are? Well, online it’s usually a Pinterest board or a Tumblr page. Back when treasures were physical, people kept them in collections called Cabinets of Curiosities.

Well, actually, (the runner-up name for this newsletter)…

The phrase “cabinet of curiosities” is a bit of a misnomer. Before they were known as Wunderkammern (cabinets of wonders), they were Kunstkammern (cabinets of works of art.) The wonders they were designed to exhibit were both works of Art (as in artifice), for example, a beautiful jewelry box made to look like a lizard, and of God’s Art (a cool piece of driftwood that also looks like a lizard.)

Viewers of cabinets of curiosities were intended to marvel at the similarities and differences of disparate objects, but those objects were collected and displayed in order to analyze the difference between the limits of human innovation and the limitlessness of God’s creation. It’s all very Renaissance. (For more, check out Wolfram Koeppe’s “Collecting for the Kunstkammer” at the Met, here.)

I say all of this to emphasize that whatever is collected isn’t representative of everything that exists. It’s included in that collection for a reason, even if we don’t always know what that reason is, or won’t admit to it. And it matters where you look to find inspiration, because what you find can determines the limit of what you think is interesting, what you’re even interested in creating.

(There’s an important point to be made here about representation, library collections policies and the fact that libraries and museums are by no means neutral spaces, but it deserves more space than I can give it here so we’re going to have to revisit it later on.)

So let’s take the premise seriously. If the internet is like a commonplace book, and vice versa, how so? Do the two ideas really connect?

“migrations of lemmings”

(yes, we are still doing Lovecraft story ideas as section headings. Never let it be said I don’t commit to a bit.)

Which is something that makes the question of digitizing images of rare books ever stickier. The images above from Octavia Butler’s notebooks come from various blogs, which lifted them in turn from a series of blog posts from the Huntington that were intended to promote the 2017 exhibition of her papers.

They haven’t been digitized yet, but you can find them all over the place on websites designed to inspire creatives, out of context. The digital hivemind that is the internet has taken these pieces for its own commonplace book and replicated them hundreds of times in the process.

Similarly, you absolutely can find digitized images from rare book libraries all over Pinterest. In fact, click on one image of a page with a volvelle and you’ll be shown a waterfall of images that Pinterest has deemed interesting to you - whether they’re the same color palette, or have a similar series of circles, or are just tagged as Olden Timey.

Everything’s on Pinterest, completely divorced from context, and Pinterest’s engine will show you exact replicas of whatever it thinks you’re interested in based on your clicks and pageviews. That poor winged pig is just hanging out there with no citation in sight.

The point is, it’ll show you what it thinks you want to see, and much of that is thin white ladies with curly hair, or low-fat recipes, or stuff you can buy. They used to just have a “following” page, then they introduced a “home” page populated with things they thought you’d like, and now the “following” page is nowhere to be found. Welcome “home”, I guess.

Pinterest, like TikTok and like Instagram’s Explore page, works based off of an algorithm that attempts to predict your interests. This is where the metaphor for social media as commonplace books kind of falls apart for me.

Just because Pinterest allows you to collect images from across the internet and organize them, doesn’t mean it’s a commonplace book. Commonplaces are about choices, decisions, the internal carpentry of your intellectual interests. Pinterest is what happens when your cabinet of curiosities turns into a WalMart. Like many online recommendation engines, it doesn’t show you what you might like, it shows you more versions of what you already have. I mean, the first autocompleted search term for “book” is “book aesthetic.”

So, how do you find what you need, rather than what you want, or what you’re told to want via an algorithm?

“members of witch-cult”

Jennifer Tinonga-Valle’s article “Pinning and Repinning: Reading Emily Dickinson through Online Scrapbook Curation” begins with an anecdote about women working in factories in the 19th century who weren’t allowed to read at work, but who would paste up newspaper clippings and poetry around their workstations in a kind of communal bulletin-board, a commonplace for the workplace. The article itself is about the poetry of Emily Dickinson, but I love that initial image because of its rebelliousness, its insistence on choice and inspiration over monotony.

The Victorian era was a time when a great deal of moralizing literature was written, especially for the consumption of women, instructing them on how to be hygienic both physically and spiritually. There will always be a push to read something Improving and Valuable, whether it’s how to be a pious Victorian woman or how to maximize your intermittent fasting schedule for the most mental energy and the sickest gains, bro. (Hello again, productivity culture. And Girl, Wash Your Face!)

This is why the choice and curation of your own commonplaces is a powerful tool against complacency, against being spoon-fed what you’re expected to like. And it’s why representation in media, in libraries and archives, and in the choice of what gets digitized is so crucial.

And it’s why I can’t believe that the NYTimes thinks I want to sign up for 8 new apps and give them my Google password in order to make a digital commonplace book, when I can just sign up for Tumblr.

It seems to be a convention in talking about social media that the platforms we’re on are great, or at least interesting, and the ones we’re not on are completely irrelevant. “Is anyone still even on Twitter?” is a question my Instagram-loving friends ask me all the time.

Tumblr is the universal “is anyone still on that?” platform, mostly because it hasn’t figured out how to successfully monetize. Nobody’s a Tumblr influencer. But because Tumblr doesn’t position itself as good or useful or, heaven forfend, productive, it allows a space for a different kind of interaction, internal to oneself or community-centered.

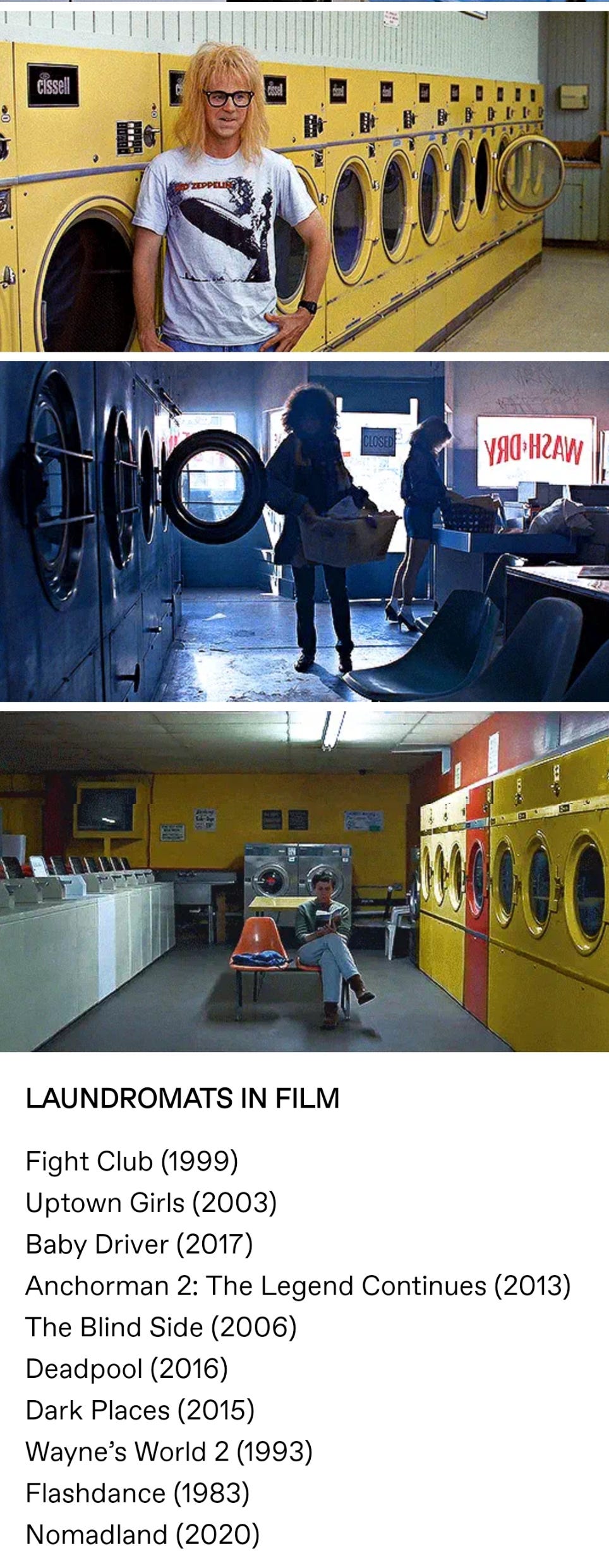

The multimedia aspect is where I really see the connection to commonplaces of old. You’ve got your traditional mishmoshes around a theme, like this collection of GIFs of laundromats in film:

Sure. Why not.

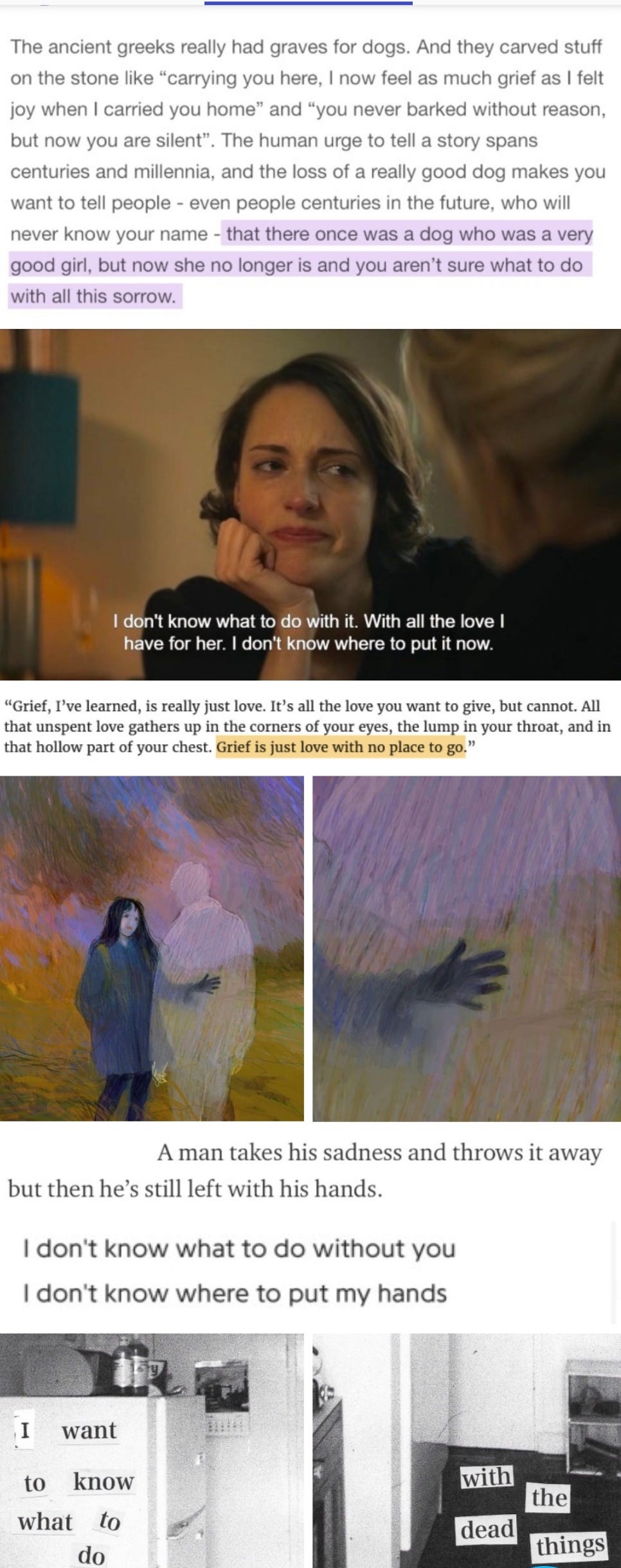

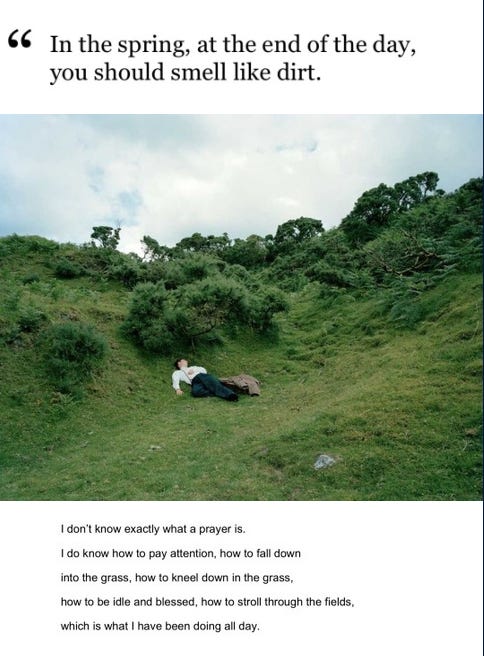

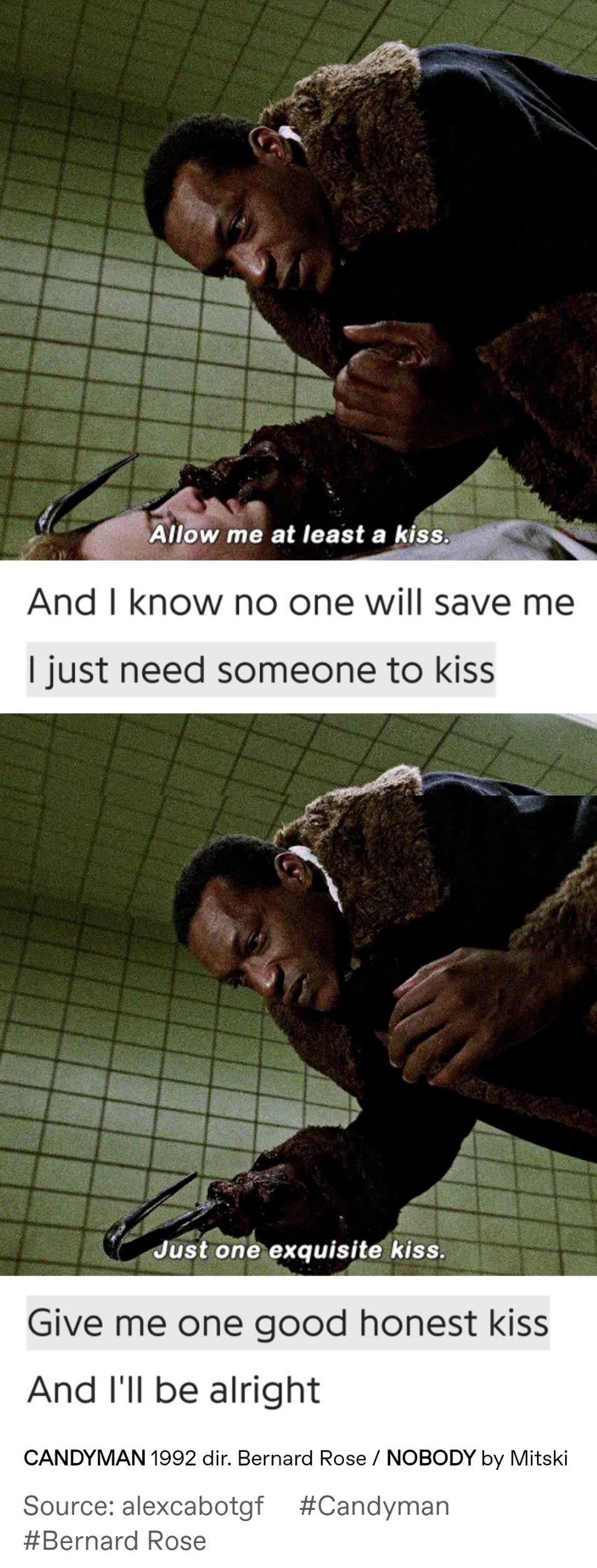

But there are also a new genre of post, which could not be more commonplacey. I think the kids are calling them “comps”, or “compilations.”

I mean, is that a scrapbook or what?

They’re not all bummers:

I mean, people get up to all sorts of stuff. My favorite so far is this one, which has to be intentionally hilarious. I think. I’m pretty sure.

I mean, maybe they’re serious. But I just love this. It’s pure commonplacing - smashing together different references and works of art around a theme, finding parallels and connections that might be insightful, or meaningless, or ironic.

It’s not even the blog that’s acting as a commonplace, with its mixture of media posts. It’s a single post itself, designed to evoke feelings and ideas around a central theme.

Tumblr’s the only place on the internet where I’ve seen this commonplacing style - collecting disparate information around a theme - and it developed, as far as I can tell, pretty much spontaneously. If the Internet at large is a commonplace book on a macro scale, here’s the proof that you don’t have to go meta to see the same functional impulse get recreated through digital media.

Crucially, to me, this kind of creation works because Tumblr still works off of a newsfeed model, where you actually pick what shows up on your dashboard yourself. (Mostly. Hilariously, as I was writing this, my Tumblr mobile app updated to a version with a new “Stuff For You” tab alongside the “Following” tab on my dashboard. So take this with a grain of salt, I guess.)

The choices you make are still a conversation with people, rather than with an algorithm. The only price you pay is maybe accidentally seeing some nice teen’s lovingly-rendered watercolor fanart of some Marvel characters absolutely going to town on each other.

And they know this, over at Tumblr. Check out their App Store description:

Tumblr has the reputation of being a little embarrassing, a little shrill, a little overwrought, a lot nerdy. Not incidentally, that is also the reputation women’s commonplace books from the 19th and early 20th centuries tend to have. (See here, here, and also here, to start.) Isn’t it all embarrassingly earnest quotations from handsome poets and some poorly-sketched violets and a story about a tea dance?

This is what took me so long to get interested in commonplace books in the first place, to my shame. The belittling of the intellectual and creative (read: emotional) output of women, especially women who are part of historically marginalized groups, is pretty much never-ending.

Which is why I’m going to take a moment to shout-out the May Bragdon Diaries, a project from the University of Rochester that has digitized the diaries of a young single woman at the turn of the 20th century. They’ve digitized not just her diaries, but also the textile scraps she saved to design a new waistcoat, the tickets to plays and shows she kept as souvenirs, her dance cards, quotations from important people in her life. If you ever wanted to look at the shoebox of mementos underneath your bed and imagine a world where they were actually organized and used to help contextualize your life, the May Bragdon Diaries are for you.

And this is part of why it’s useful to actually think about what it means to compare commonplacing to social media.

Social media is social - public in a way commonplace books never were, even if they were shared between a circle of acquaintances. Measuring and monetizing visibility is another way social media distorts the interior project of commonplacing.

The internet is just people - that’s why it’s so good and so bad and so fast and so infuriating and so dangerous and so wonderful. This is why TikTok has such power, why “influencer” is a job. But that false sense of intimacy also hides the crucial mechanism by which these things come into our lives.

If you ever wanted some inspiration for surprising yourself into creativity and away from the algorithm, might I suggest David Bowie and his Verbasizer?

Bowie would use the cut-up technique to write his lyrics, which is where "I’m an Alligator” (the first line in Moonage Daydream) came from.

And later, in the 90’s, he created the Verbasizer to automate the same kind of process.

This isn’t quite keeping a commonplace book, but it’s taking found phrases and smashing them together in much the same way as a commonplace book juxtaposes different quotations and verse. Crucially, commonplacing isn’t just about being a magpie, picking and choosing. It’s about the discovery those choices engender. It’s about how we surprise ourselves, and, contrary to the arguments that social media is just a commonplace book for the digital age, digital tools are being engineered to make it more and more difficult to do just that.

“transposition of identity”

When I started a Tumblr, it was medicinal. I was setting myself the task of acquiring a remedial personality. I wanted to like what I really liked, not what I felt I was supposed to like, what it was cool to like, what would make me seem interesting and worldly. I wanted to dive into embarrassing interests I thought I’d left behind as a child, and the offbeat things that caught my fancy that my friends and acquaintances didn’t understand.

But the things I really wanted to keep and hold close to my heart I didn’t just keep online. I kept them on my computer, but also in journals, in scrapbooks, in Google docs, in the Notes app on my phone, in desperate e-mails to myself on my lunch break.

And when I talked to my family about it, my mother showed me her organized three-ring binders of newspaper clippings, poems, and sketches organized by theme, and my grandmother’s hand-pasted comic-strip scrapbooks with everything that caught her fancy, made her laugh. My Grandad keeps commonplace books of humorous anecdotes to share at his retirement home. Everyone’s trying to hold onto something.

You know that feeling where you’re driving past a familiar location and you remember something big happened to you there, but you don’t quite remember when it was, or who was there, or what really happened? You just have your now-memory, overwriting all of the bits of what really happened that your brain needed to forget in order for you to remember your 89th password of the week?

You know that feeling that somehow something used to be important to you, or at least it was important to the person you used to be, but you can’t quite put your finger on it anymore?

You know when you have a brilliant thought in the shower, or in traffic, or at 3AM, and you promise yourself you’ll remember it but you never quite can?

Commonplace books are medicine against all of that.

I mean, all creative output is attempting to fix a feeling or a memory or a moment into the physical world like a pinned butterfly. But commonplace books don’t have to mean anything to anyone else - just to you.

They don’t have to make a statement, or be intellectually cohesive, or say something profound about the zeitgeist. But they can remind you of who you have been, and recall yourself to who you are now, and make you perhaps more hopeful about who you’re going to be.

The value of the commonplace isn’t for the Great Creative Mind, or for the Political Whoevers. To me, it’s a mistake to think that investigating the condition of living is the province of a few intellectuals or creatives.

When you visit a rare book library to leaf through someone else’s commonplace book, you find out what they paid attention to, what they thought they ought to keep, and if you’re really lucky, what they thought they ought not to keep, but did anyway.

The organization of commonplace books isn’t the point. Or, rather, it’s the whole point. It’s interesting HOW we organize, and WHETHER we organize our thoughts and influences, because it shows us what values we’re directing our thoughts towards, and what we’re drawing from our intellectual environments.

The act of noticing is reason enough to keep track of the things that bring meaning to your life. The behavior that is investigating the conditions of life isn’t FOR anything, doesn’t make us money, won’t necessarily create the next big best-seller. It’s not a lifehack. It’s just a life.