Hi, everybody! It’s been a while. I hope I’m finding you all adequately cool, with your iced beverages of choice at the ready.

First off, I’m sending this the week of Juneteenth (the federal holiday, the day itself was last Sunday). If you’re able, this would be a good week to contribute to Black-led community advocacy groups in your area. If, like me, you’re in Chicago, this might be a good place to start.

This week is also RBMS, the big U.S. conference for rare books and manuscripts and special collections. Here are some things to know:

I'm giving a lightning talk on Thursday, June 23, at 2pm CT! I'll be talking about this newsletter, why I started it, why I think newsletters are effective and what they can teach institutions about how to meet people where they are online. I'm really proud of it, and really terrified to watch a recording of myself.

There are a TON of cool lightning talks going on, and if you’re planning to attend RBMS I very much hope to see you there. I might have snooped around in the Google Drive a little bit and seen what other people are talking about and there's a lot of good stuff going on.

Please come say hi whether you’re going to the conference or not! I'll be hanging out on Twitter all week @Katie_Bergen and @TheRareCommons, and tweeting about #RBMS22 a bunch.

I swear I'm a real human person and not just an extremely temperamental email robot, and a virtual conference is not the BEST place to make that clear, but! If anyone's going to be at ALA, I’d love to say hi in person.

I'm still figuring out my schedule because it's my first ALA (!), but I printed up some extremely rad business cards and I'd love to see any of you who are going to be in the DC area this upcoming weekend. If you want to grab a coffee and talk about online outreach and digital special collections, I would love nothing more!

But before we get to all that exciting stuff, I just wanted to give you guys a mini newsletter (as “mini” as these ever get) to whet the appetite for what’s coming. I've been busy developing the next phase of The Rare Commons, and I'm excited to show you all what I've been working on, but in the meantime, let’s talk about Weird Medieval Guys on Twitter.

WEIRD MEDIEVAL GUYS

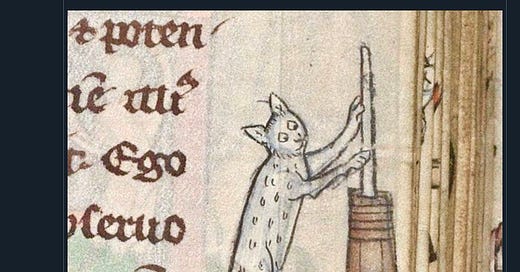

@WeirdMedieval’s brilliance lies in taking snippets of medieval manuscripts, usually marginalia or doodles, and presenting them without context a few times a day.

Scrolling through Twitter usually looks like a picture of a dog in a spider costume, the most devastating possible thing that could possibly happen, nearly breaching the boundaries of what your mind can conceive of, horror-wise, and then a hot take about the new Top Gun sequel. So there might as well be a picture of a little frog blowing a trumpet in there, too. It’s no less odd than anything else you’re seeing, plus it’s very cute. No wonder the account’s so popular.

But there are things about it that… irk me.

Now, it’s time for Katie’s Finger-Wagging Screed About Citations. Everybody, keep your hands and feet inside the vehicle while we all read this collectively in one breath and get it over with:

Saying something like “France, 13th century” doesn’t mean a whole lot to someone who doesn’t already know their Carolingian miniscule from their Textura, especially because that style of “citation” was developed for graphic art on paper — when you say “17th-century Dutch” or “Japan, 19th century”, people have Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring or Hokusai’s The Great Wave in mind and so can get an idea of the context — so just saying “France, 13th century” about a marginal drawing in a manuscript won’t tell you if it’s from a book of hours or a recipe book or a ledger or an antiphonal, or how big the book is, or who used it, or whether it’s a copy, or if the drawing in question is really a picture of a cool bat some student in 18th-century Spain saw the night before and has now doodled for his classmate, in which case “France, 13th century” might apply to the original book but has nothing to do with the actual marginal drawing in question.

Citations are a pain in the butt, but they should function to help us make sense of what we’re seeing. Don’t you want to know what it is you’re looking at, what it’s for, what it lives next to? Why is the pelican or the cat churning butter even there? Is the available citation going to help you find out?

First, we have to talk about the Met Gala.

TEXTILE CONSERVATORS, LOOK AWAY NOW

If you're on the Internet at all you will have seen this year's Met Gala, whose theme was, I’m pretty sure, American Fashion: Good for U.S.!

Kim Kardashian wore the dress that Marilyn Monroe wore to sing “Happy Birthday” to JFK. She didn't wear a replica. She didn't wear a dress inspired by it. She wore the actual dress.

And I mean, there's a whole tangent I could go into about Marilyn Monroe's physical legacy, possessions, name, image, and voice being broken up and sold for profit against her express wishes, but for now we’re focusing on the one dress.

The whole point of Marilyn Monroe's dress was that it was made to her exact measurements and skin color to create a shockingly realistic nude illusion. That was the function of the garment as it was originally worn.

The function of the garment when Kim Kardashian wears it is not the same, because it was made for a particular body, and that is not the body that Kim Kardashian has because she didn't resurrect Marilyn Monroe's corpse, which is probably for the best.

And so the whole intended effect of the dress doesn't work. It just becomes a woman in a beige dress with rhinestones.

But the nakedness wasn’t the point this time. Kim Kardashian has looked much nakeder on the red carpet, and probably will again. For her, the value was in the shock and awe of seeing a unique archival garment made to the exact measurements of one of the most celebrated and fetishized bodies of the 20th century being worn again, fitting one of the most celebrated and fetishized bodies of the 21st century (so far), connecting her indelibly with the original wearer. That's what she was going for. And that's what she got. And that's why she didn't wear a replica on the red carpet.

Which, sure. Go figure. Duh@obviously.com. I’ve lost more sequins sneezing at a bar mitzvah, much less climbing the stairs of the Met. The owner of the dress denies any damage has been done to the dress by its recent outing. (sure_jan.gif) I believe Kim Kardashian was as careful as she could be, and did her best to be respectful of the dress’s age and delicacy as she wore it.

But it doesn’t matter.

Why not? Because of the Betty White principle.

THE BETTY WHITE PRINCIPLE

As someone whose favorite thing in the world is to bring people into the library and let them get up close to Touch and See and Smell and Experience Books and Manuscripts, I often worry that my enthusiasm for getting our collections out for show and tell is making all my conservator friends lose their minds. And it is! They’ve told me so.

Many of the objects in our collections have been around for hundreds of years, sometimes thousands. They've made it this far through fires, mold, earthquakes, neglect, sun exposure, and that one reader who keeps trying to sneak Jolly Ranchers into the reading room and then lick their thumb as they turn the pages.

If you think about that chain of quasi-miraculous survival, you do not want to be the person who introduces a new mark of use or wear to the object. I mean, it happens, and then we have to console ourselves with the fact that in 200 years someone will probably find that nail polish smudge fascinating, if it hasn’t eaten through the page by then. That's just how history goes.

When you think about whether to allow someone to use a rare book, you have to imagine yourself casting Betty White. She had a vibrant career spanning almost 70 years, and was still working and still vital almost until the very end (RIP Betty.) How did she manage it? A combination of good luck, good genes, and common sense.

You can't put her in every single Michael Bay film. She's not going to do great with explosions. You can't send her to Antarctica, and also you can't have her host every episode of Top Chef because the filming schedule and eating requirements are going to exhaust her, because she is a Woman of a Certain Age.

And so you have to think very carefully about how and when you deploy the majesty that is Betty White without making her unable to continue. Similarly, when people complain that you’re not making your copy of the Gutenberg Bible available today, maybe the Gutenberg Bible has been out three times already this week, which is already way too much.

This is why I hate the idea that there's a feud between access and preservation. To my mind, they're the same thing. I’m not the first person to have made this point, but it’s always made sense to me that you have to preserve objects to make it possible for people to access and use them, otherwise what’s the point in preserving them?

More importantly, if no one sees them or uses them or understands their significance, no one’s going keep paying to preserve them. Therefore, making things accessible for as many people as possible, for as long as possible, is what preserves their existence into an uncertain future. This is not news, almost everyone in the field of special collections knows this.

Kim Kardashian’s Met Gala mistake wasn’t being careless with the dress in the moment, it was using the dress at all. It’s a clear violation of the Betty White Principle.

Kim Kardashian wearing a unique, irreplaceable textile artifact, even for just 20 minutes on a red carpet, is not preserving Marilyn Monroe’s one-of-a-kind dress for the maximum amount of people and/or time. It’s the archival equivalent of making Betty White do her own stunts for the new Mission Impossible 8: Mission Impossible to Mars Impossible. Even if it’s only 20 minutes, it’s 20 minutes of shooting Betty White into the merciless vacuum of space, and she’s inevitably gonna undergo some wear and tear.

This is what makes digital projects like Weird Medieval Guys so great, because they get the contents of rare books and manuscripts in front of more pairs of eyes than any library could ever accommodate, without damaging any of the physical sources. Digitization! Hurrah!1

But with citations like “France, 13th century”, how is anyone meant to find out what exactly they’re looking at? And without context, how can these weird little guys ever be more than an amusing sideshow, no more meaningful than a cat playing the piano?2

THE URL AND THE SHELFMARK

I don’t want to come down too hard on Weird Medieval Guys, here. They’re trying to do their due diligence. There will often be a URL or a shelfmark, or both, accompanying each image.

Twitter citations are interesting to me, because they represent the bare minimum, lowest-common-denominator citation — the thing you put there because someone said you should, but you’re not really sure about formatting, but you want people to basically know what it is.

So, when you’re looking at

“MS. Arch. Selden. A. 1 fol. 8r” (a shelfmark)

or

which one’s more useful?

Probably the one in a format you’ve already heard of and know how to parse, right? Let’s hear it for the URL. Just click on it. Boom. Done. Phew.

But everyone here’s gotten a “404 Not Found” notice, right? And if your Weird Medieval Guy is sourced to somewhere like Wikimedia Commons, that error message is suddenly way more likely.

The line of gibberish that will never let you down? “MS. Arch. Selden. A. 1 fol. 8r”

I love a shelfmark. In the early days of libraries, you would make a note of where on the shelf a book was, and mark the location on the book. And, much like a URL or a permalink, it was meant to be this unique identifying tag that showed where something was and allowed you to recall it when you want it.

My first paying job in libraries was at the Bodleian, and though they don’t like to say so, some of their oldest shelfmarks just have to do with the physical location of books inside the room, usually Duke Humfrey’s library, the OG Harry Potter library, where I spent one heady (read: dusty) autumn boxing up old card catalogs. It’s that simple.

Unlike a URL, a shelfmark isn’t contingent on site redesigns, or who the new webmaster is. It doesn’t relate to the iteration of the book that exists on the web, but the actual physical book itself. (I’m certain there are metadata markers that identify the digital iteration of the book, too, but I can’t find them/am too scared to try. Pay your digital preservation staff more.)

So as long as you know your shelfmark, your handy neighborhood search engine can find you a catalog entry or a finding aid or, if you’re lucky, an image of whatever disembodied fragment of really old book in JPEG form you might be looking at. But you can’t click on a shelfmark, so that’s a drag.

Basically, (VERY basically), information management is the job of remembering where things are and how to get to them. Shelfmarks help you do that, and URLs don’t… always. And that's what makes the Internet such a good time for everybody! (heavy sarcasm)

But throwing contextless book-chunks out into the world isn’t a new thing - it’s called bookbreaking, and people have been cutting up manuscripts for pleasure and profit for centuries.

IF YOU WANT TO MAKE AN OMELETTE, YOU’RE GONNA HAVE TO BREAK SOME EGES

Otto Ege (pronounced “Eggy”) was a 20th-century bookseller and medievalist from Cleveland who cut up medieval manuscripts to sell in portfolios, like a kind of special collections appetizer platter.

He made more money, of course, but he maintained that part of his mission was also pedagogical, if not philanthropic. Instead of being locked up in libraries, these pages could be shared with far more people than ever before, spreading learning far and wide. Also did I mention he made a bunch more money than he would selling the entire books?

Should the cultural heritage that libraries preserve be accessible to as many people as possible? Absolutely. But cutting pages free also cuts them loose from the context that gives them meaning. Ege appreciated these fragments as art objects, but that divorces them from every other way to study and create new knowledge from an old book.

Pages are given context by their neighbors, collected into a book. Books are given context by their neighbors, gathered into a collection, and collections are given context by their shelfmates, creating a library (or an archives). (Yes, “archives” is plural-singular. Go argue about it with an archivist.)

This is why there was such a hullabaloo last year about preserving the Honresfield Brontë Library intact: each layer of context allows us to learn more, to make more meaning, to deepen our understanding. (Oh, look! Here’s that “Marilyn Monroe’s possessions and legacy getting sold off for parts” tangent I wanted to go on.)

Many of the images that are featured on Weird Medieval Guys are from illuminated medieval manuscripts, many of which use very precious pigments and inks and materials and which, for most of their history, have been kept locked away very safely, very securely and very few people could access them, which is why they still exist.

Now they’re available online3, which is incredible, but they’re still getting broken up into little contextless bite-size images, and for similar reasons: beauty, sensationalism, the thrill of seeing an artistically detailed drawing of a pig with wings chasing a group of nuns.

So can we consider orphaned, citation-bereft images of digitized library materials as “broken” digital books, if they can’t be easily connected to the original source, or holding institution? Are good citations enough to give them the context to help make them “whole” again? And is “whole” even a useful goal in a digital age?

Important caveat: digital book breaking isn't permanent. If you cut something with scissors, that's a done deal. You can tape it back together4, but it's not going back the way it was. Digital books aren’t broken because they’re individual images, they’re broken when they can’t be traced back to the context that gives them deeper meaning. This is where thoughtful digital exhibits can shine.

Let’s take a moment to highlight the work that the fine folks at Fragmentarium are doing, studying physical manuscript fragments and in some cases tracing them back to the original work they came from. This kind of work would be much more difficult without digital technologies, because you're putting books back together where one fragment might be in Japan and one might be in Chile and one might be in Germany.

The fragments aren’t physically back together, but the digital linkages that connect them allow us to understand how they came to be, and now they exist in an ever-richer web of connection that only the digital can achieve.

SOAPBOX TIME

And that's why these pop history accounts do get under my skin a little bit, because the teaching and learning side of bookbreaking that Ege used to justify himself isn’t taking off to the same degree in the digital space.

If the point of libraries and archives is to facilitate the flow of information, that flow has gone from a trickle to a full-on firehose in the digital era. It’s an absolute deluge, which is why our job is more important than ever.

The digital space is all about linkages and connections, from hyperlinks to retweets to Tiktok duets. It's all about relationships from one digital “thing” to another.

This is why the immense amount of effort, time, and money that goes into making 100,000 new manuscript images available online is only the beginning of our work in the digital space. (Metadata librarians, we do not deserve you.)

And it’s why the hard work, planning, strategizing, and fighting for funding that has gone into creating online library exhibits and digital projects makes me so focused on helping those projects get their moment in the sun right alongside Weird Medieval Guys. The context, connection, and nuance that gives digitized special collections meaning is already there, it just needs to be shown off where people will see it.

Social media management is difficult, complex work that is consistently undervalued, and it’s also our key to meeting patrons and the public where they already are, whether we’re mid-pandemic or (hopefully, someday) fully out in the world again.

It’s certainly not more important than the core activities of our field (curating, cataloging, archiving, conservation-ing, public services-ing) that are also incredibly difficult and deeply underpaid. But I believe it’s a good way to get those core activities funded, and funded more consistently and heartily, into the future. Lots of smart people are already doing great work to help their institutions have an impact on social media, but I think we’re just getting started.

Want a healthy donor base in 10, 20, 50 years? Let’s use the work we’ve already done in the digital space to make our value clear to the people who already love us, and to those who don’t know about us yet. I certainly don’t think we need to cede the majority of the cultural impact of our institutional assets to pop history accounts, no matter how cute that badger playing the accordion might be.

Boy, that soapbox got comfortable for a minute there. Just bear with me while I wipe the foam from around my mouth, would you?

That’s better.

If you’re interested in talking more about a strategic plan for your institution’s social media, if you want to plan a Twitter campaign for your next big exhibit, if you need some hapless jokester to write your newsletter, let me know!

I’ll be hanging out my shingle this summer, and I’d love to talk to you about what your institution needs and how we can work together to grow your reach and bring your online resources and projects to life.

In the meantime, do come say hi at RBMS or in DC or on TWT (it was the only one without an acronym), and I’ll be back with more Rare Commons: The Newsletter later on in the summer.

RED FLAG: Never trust anyone who uses the word “digitization” as though it’s one thing, much less one magical thing that’s going to solve all of our problems and make libraries obsolete.

Just kidding. Obviously Keyboard Cat is an indelible part of our unique 21st-century cultural heritage and worthy of preservation and future study. Sorry, Keyboard Cat.

Wait a minute, let me not gloss over “available online.”

Digitization is a massive umbrella term that covers a multitude of processes and all of them are time consuming and difficult and involve metadata and are terrifying and I just would like to say again , pay your digital preservation people more money and give them more funding to do the work that they're doing because oh my goodness.

“PLEASE, NOT THE PRESSURE-BASED ADHESIVE” - every conservator ever