Slow Your Roll with the Infinite Scroll

Fun with form and function!

*NB: As with last month, I have not been able to keep a lid on it, so this e-mail may well exceed the length limit of your inbox. Make sure to click the link to read the entire message at the bottom of this e-mail, or just read it over at the website.*

CHECK YOUR POSTURE

Are you reading this on a desktop computer in your office? (I won’t tell.) Do you have your laptop open on a desk, or are you reclining, cross-legged, on a couch, scrolling on your tablet? Are you, perhaps, hunched over your phone, or holding it an inch above your face as you lie in bed? No judgment here.

But it’s worth thinking about, right? So often we think about consuming information, and the ways in which we consume it, as though they’re completely divorced from the body.

We think about our eyes and our brain, mostly: how fast we read, how much we skim, how short our attention spans are. And then we complain about strained shoulders and text-neck and carpal tunnel, without thinking about the fact that our entire bodies are implicated in the act of consuming information, as they are in everything we do.

The digital hardware we use is designed to be picked up and carried, and the screens manipulated with our fingers. I think we tend to think of touching what we read as a modern thing - the touchscreen, with all of its pinching and spreading and swiping. But hands have been a part of how we read books ever since books were… books.

How does the format and shape of what we read affect how we absorb the information itself? And what does that have to do with the fact that it’s really hard to find a scroll exhibit online that you can actually… scroll?

BOOK HISTORY DANCE BREAK

When we think of digital text supports, we think of screens, right? The Black Mirror. The glowy thing that the words appear on. The GUI (graphic user interface).

It’s square! It’s shiny! It’s maybe a little rounded at the corners. In short, it’s a tablet.

Know what else is a tablet?

This guy:

(A person funnier than me on Twitter called this The Forbidden KitKat, and I can’t say I disagree.)

We talked a bunch last time about how parchment was super expensive and paper wasn’t a thing in Europe for many thousands of years, so what were you meant to do if you were trying to learn how to write? Well, meet the wax tablet. And the clay tablet. And the stone tablet. Tablets for everybody.

Tablets are the easiest thing to write on and read from. But what happens if you have a lot more to say than will fit on a tablet? In that case, can I interest you in the scroll, aka the Tablet Plus? It’s got bits on the end that you can roll through to get to the part you want.

This is how scrolling works online, too. You have the little bit of information that you’re focused on at the moment, and everything else is tucked neatly away in the code, with the potential to be called forth by your scrolling fingers as fast as your internet connection can do it.

Why did scrolls go out of fashion? Well, they’re great to read slowly over time, but it’s hard to jump back and forth between different sections (as you know if you’ve ever tried to scroll back to That One Tweet on someone’s timeline.)

It’s also hard to carry scrolls around without squashing them. You’d need a whole arrow-quiver shoulder-sling situation, and a roller to put it on if it’s really long, which gets heavy. Enter the codex.

“Codex” is just the word for what we think of nowadays as a book - a rectangular block of pages sandwiched between two boards, with a spine. The word comes from “caudex”, which is Latin for “tree stump”.

There’s a whole school of thought that says that the codex exists because Christians wanted to go from town to town proselytizing, and you can slip a codex into your pocket much more easily than a scroll . Also, if you want to cite a bunch of different excerpts to make your point, you can stick your fingers in between the pages to hold your place - the original bookmark.

If you want to impress the biddies at your book club, this is called ‘discontinuous reading’, as opposed to reading something cover to cover. As in, I read Chapter 1 and Chapter 19 and Chapter 5 and I got the gist, Janice, so pass the cheese straws already.1

The point is, books are made for hands as well as eyes, and just because many books now live online, doesn’t mean we’re not still trying to manipulate them.

(That word - manipulate - has the same Latin root as manual - “manus”, meaning “hand”. What’s a manual? A handbook! And “digital” comes from the ten digits on the ends of those hands, which we use to count with. Numbers -> Digits -> Digital! I almost called this newsletter “The Digital Manual” and was only saved from myself by a forceful intervention from concerned friends and family members. I still think it’s a funny name.)

This brings us back to scrolls: if the modern smartphone is a tablet with an infinite scroll inside it, and all of the pocket-slipping convenience of a codex, complete with enough finger-tapping, pinching, and scrolling for an Olympic facial massage team, then why don’t online exhibits about scrolls make use of our devices’ native scrolling functions?

Scrolling is native to the digital world (at least in the post-command line days in which we live), so there must be a bunch of Big Fancy Library Scroll Exhibits somewhere online, right?

Maybe there are, and I missed most of them. If you’re the person who made/developed/knows about/can’t believe I didn’t include The Big Obvious One, please feel free to send it along and I’ll put it in an addendum next month with my apologies.

But what I did find is, I think, just as interesting in its own way. Looking at what books attempt (and sometimes fail) to do, both online and in physical space, can be just as illuminating as looking at where they unequivocally succeed.

Let’s dive in, shall we?

DOOMSCROLLING

Here’s something to think about: if you’re setting about reading a scroll, are you going to read it horizontally, or vertically? Are you going to bring it down in front of your face like the town crier reading a proclamation about Cinderella’s missing slipper, or are you going to scroll through it from side to side like a panorama?

Here’s a copy of the Book of Esther held at the University of Sydney. As you can see, the first image is of the closed scroll wrapped around its wooden roller.

The rest of the scroll is laid out in the viewer as pages, like this:

You can see at the side that there’s visible stitching where the parchment page was attached to the previous one, to form a continuous scroll. Like its physical counterpart, the online Book of Esther exists as separate pages. Unlike the physical scroll, the digital one hasn’t been stitched together.

Hold that thought.

Here’s a section of the Hōrai no makimono, from the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois:

This is another horizontal scroll, depicting a Japanese tale from the Muromachi period. If you click on the link above to view the digital version on the Illinois website, you’ll see that the first image is of the entire roll, digitally stitched together. You can zoom in, and click and grab different sections to move across the roll, or you can see the entire thing at once.

I’ve had the privilege of seeing the real-life roll spread out in the reading room during grad school, and it’s both extremely beautiful and very terrifying. Beautiful because, well, look at it, and then imagine how the colors come to life when you’re looking at the physical object. And TERRIFYING because you are NOT going to be the one who lets it get damaged on your watch.

Most scrolls aren’t meant to be rolled out and read all at once, including this one. You’re meant to scroll through the narrative and the images as though looking at a slowly moving landscape. And although it’s possible to unroll large sections of this manuscript (if you’re VERY careful), you can’t see it all at once in physical space. But you can, digitally, due to the extremely painstaking and diligent work of the U of I digitization services team.

(You can read more about the process of digitizing Hōrai no makimono here, including custom-made cradles and digitally eliminating shadows and all kinds of tricky practical concerns, as well as a buttload of metadata.)

My point is this: although it’s possible that these physical copies of both the Book of Esther and the Hōrai no makimono are around the same age (give or take a century or two), their digital counterparts have been made accessible in different ways.

Although you can still see where sections of scroll have been joined together in the Hōrai no makimono facsimile, the emphasis has been on eliding those joins, and creating a digital object that can be accessed in a way the physical object can’t be: all at once.

But because most books are codices, most digital image viewers for libraries are set up to click or flip between independent images of pages. And although text is easy to scroll through on computers, creating a bespoke image scroller for each scroll book just isn’t feasible.

Slicing a scroll into pages so that it fits into an online viewer feels like it should be anachronistic. Leaving the Book of Esther in parts seems like it should take away from the experience of trying to recreate reading from the scroll itself. But the Book of Esther is read in sections, not all at once, as is the Hōrai no makimono.

A NICE GESTURE

“But Katie,” I hear you protest. “What about VERTICAL scrolls?”

It’s true. Most online scrolling happens vertically, like the scrolling you’re doing to read through this newsletter. So, maybe horizontal scrolls aren’t going to fit seamlessly into a digital environment (and, in fact, looking at those seams is instructive.) But what about scrolls that are read vertically?

Feast your eyes on this beauty, Bodleian Library MS. Aeth. f. 4 (R):

If you click through to the tweet, you can see just how massive this scroll is. If you follow this link, you can mess around with it yourself.

Digital tools have made it possible to unscroll this entire scroll, even though the physical object itself is very old and very delicate.

(This isn’t the only set of scrolls the Bodleian has digitized, either. You can read more about their work on their delightful digitization blog, Booksquashing, here, and at Daniel Sawyer’s Rolling History project.)

But what I find most interesting is that the computer’s native scroll function (two fingers moved up or down the trackpad), has been co-opted as a zoom function by the image viewer.

In order to move up and down the length of the scroll, or read through it, you need to click and grab sections of the image and drag them up and down your screen. This isn’t unusual when looking at images or maps online. But… texts?

Similarly, the Digital Critical Edition of the Canterbury Roll, held at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand, is a genealogical roll tracing the lineage of the Kings of England from Noah (who knew?) to Edward VI. You can use your cursor to click-and-drag across the entire length of the roll, and select highlighted sections to read in closer detail. Everything’s been transcribed and translated in Latin and English, with notes and addenda. It’s a colossal amount of work.

But that raises a question - in its online iteration, is this text primarily a text, that you would scroll? Or is it primarily an image, that you click and drag around? What is this digital version intended to be used for?

When I went looking for scrolling exhibits that focus primarily on text, my mind kept returning to this NYTimes project published last month. I call it a project because it’s not quite an article, and it exists primarily as a digital object.

I don’t know how they dealt with it in the print edition of the paper, but in its digital form it’s a scrolling analysis of a poem by Elizabeth Bishop. It’s a close reading of the poem itself, and how it reflects Bishop’s life experiences.

As you scroll down the page, different sections of the text are discussed and highlighted. The analysis jumps backward and forward in time, leading the reader through a narrative that includes images both of Bishop herself and of various drafts of the poem, showing us how she made the precise word choices that led her to the poem’s finished form.

The presentation is essentially a scroll of captioned images, and as we read through it, the images of the text zoom and recede, focusing on particular words and phrases to illuminate the structure of the poem itself.

I call this project a scroll because it functions as a complete narrative that flows through an argument, without any breaks. It can’t be read discontinuously — you can’t even look at the whole thing at once. You have to pass through each section in order to get to the next. Rhetorically, it’s totally a scroll.

Once codices became the standard form for books, scrolls were often chosen as a physical format that helped to reinforce rhetorical continuity. For example, the Chronique Anonyme Universelle (Ms. M. 1157), is a genealogical roll held at the Morgan Library.

The Chronique isn’t a traditional narrative, like the Book of Esther or the Hōrai no makimono. It’s a genealogy, stretching from Adam and Eve all the way to Louis XI of France, for whom it was made. It’s one complete thought, intended to stretch out across time as an unbroken record. (Harvard’s Houghton Library has a useful overview of the history of scrolls.)

Scrolls mandate your attention and don’t allow for discontinuous reading - it’s hard to jump from one place in the narrative to another. The NYTimes project is an article that leads you by hand through an argument - you don’t have to search the text for what you need, or go back and check. It’s hand-presented to you.

On the other hand, if you click on the link to explore the Chronique, you’ll be able to use the viewer to scoot backwards and forwards over its entirety. However, the dots which mark your place at the bottom (they look a bit like the dashes in an Instagram story) show you that these are pages, with a cool animation that attempts to replicate the feeling of reading a scroll.

But it’s still chunks, man. The scroll bar at the side of the page only works for the chunk you’re currently on.

The point I’m trying to make, here, is that considering how we can interact with a digital object or text, i.e. click-and-drag or scroll-with-cursor, tells us something about what information is considered important about whatever it is we’re looking at.

The format of a book tells us how to read it. Scrolls are for reading continuously, running through the entirety of a narrative or an argument. Codexes are for flipping between pages, taking bits and checking back to just confirm something, and then yelling “You’re WRONG, Bernice!”

What you can do with information depends on the format that information comes to you in.

In the NYTimes piece, we can’t zoom in on Bishop’s manuscript drafts to get a closer look at the words she crossed out, or her handwritten notes to herself, or the particular shape of her lover’s eyes in a photograph. We can’t use this project to consider the sheets of paper that make up her various drafts as objects with a material reality, because the focus is on her words. More than that, it’s on the authors’ analysis of her poem.

By contrast, although the Canterbury Roll is about an actual roll, you can’t scroll through it as you would be able to with the physical object. But the digital Canterbury Roll doesn’t exist rhetorically as a scroll, but as a research tool that you can navigate freely. Even…. discontinuously.

SCROLLS IN REAL LIFE

If you want a digital facsimile of a scroll that actually functions in the way a scroll does, this print-a-scroll is a pretty cool option:

It’s tricky, though, right? In order to get the full benefit of the print-a-scroll, you’ve got to print out individual pages and tape them together, much as leaves of parchment would have had to have been joined together to make the original scroll. Getting a scroll to work like a scroll isn’t just difficult in the digital world, but in the physical world, too.

People have had trouble trying to use scrolls to support information since before digital tools existed. Take Matthew Paris, for example. As a Benedictine monk in 12th-century Canterbury, his life was pretty much confined to his monastery. But his magnum opus was a work called the Chronica Majora, now held at the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, in which he created an itinerary map of the route from Canterbury to Jerusalem.

We think of maps as wayfinding devices, but this was a map that wouldn’t help you find your way if you were lost, at least not physically. Instead, it was designed as a tool for spiritual contemplation, so that monks like Paris could mentally and spiritually imagine themselves following the route to Jerusalem, through all the great cathedral cities of Europe, without leaving their cloisters. The map is a ribbon of parchment, laid out as a route you could follow with both fingers and eyes, complete with flaps that open if you wanted to take a detour to, say Reims, or Cologne.

If you look closely, you can see that this folio shows the route to Paris, complete with the Seine. The red route that takes you from place to place is labeled “jurnee”, or “journee”, meaning a day’s worth of travel (like a journey), showing you just how long it would take someone making the physical pilgrimage to get from place to place.

The itinerary itself is read from the bottom of the page to the top, then starting back at the bottom for the second column. Even though Matthew Paris chose a format that would surely work best as a scroll, he’s constrained by the codex format and instead has to lay out his itinerary in strips that fit onto separate pages. (Much like our friends at the University of Sydney digitizing the Book of Esther into images of pages.) (It has been argued that the map was designed to be cut out and followed like a roll, but the Chronica survives as a codex, so that’s what we’re going with.)

Format and information are inextricably tied together. Matthew Paris chose a format that should work in the way a scroll does - as the unrolling of an unbroken narrative of information, making the journey to Jerusalem into a “Greatest Hits of Christendom” world tour. But it had to exist as a codex, because that’s how books were made at the time.2

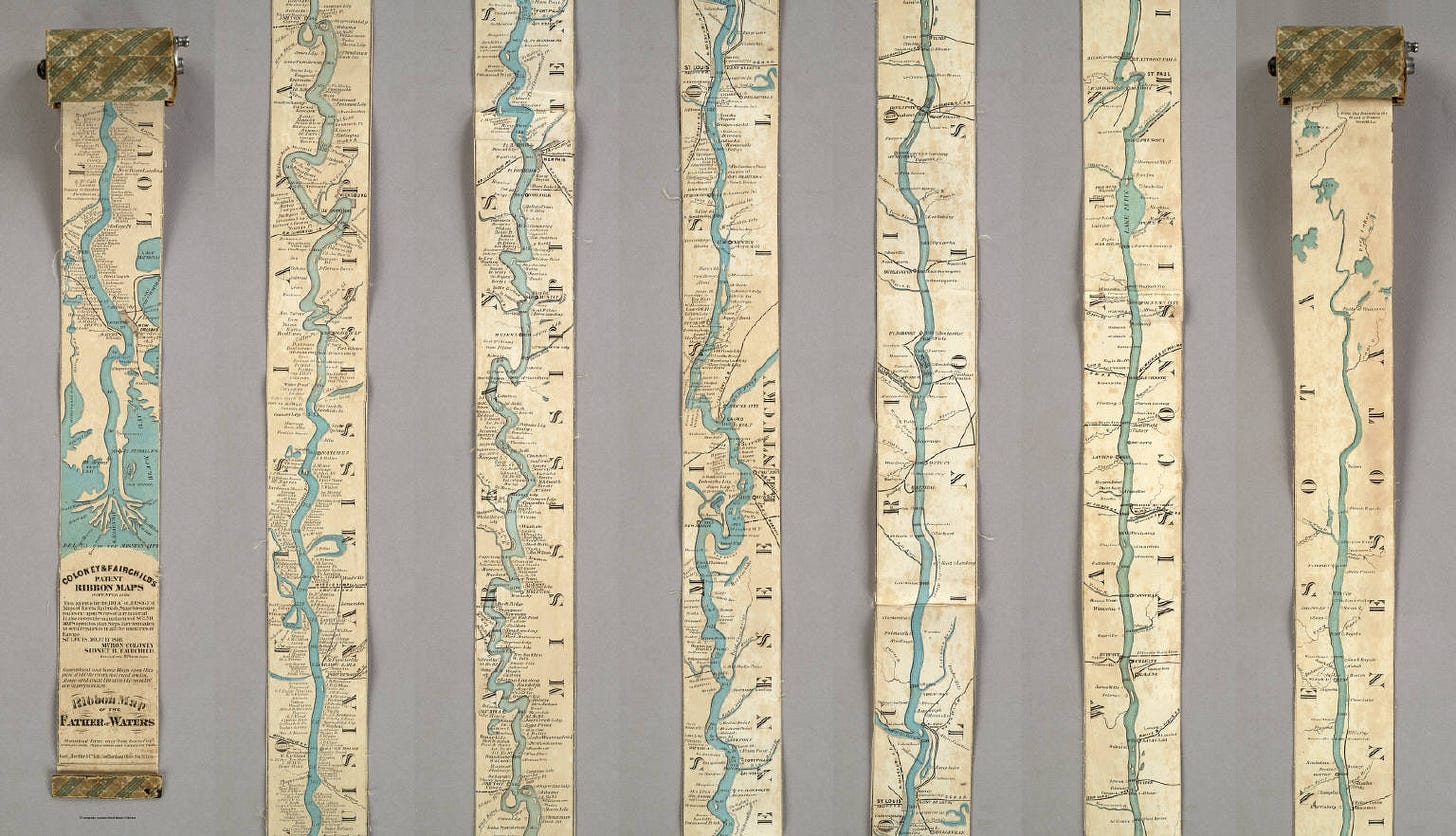

What would Paris’s itinerary map have looked like if it had been cut out and rolled up? Maybe something like the Ribbon Map of the Father of Waters , a tourist map of the Mississippi designed to be unrolled as a kind of panoramic companion document as you steamed up the river from New Orleans to Minnesota.

As you can see, you can’t possibly use this map to navigate. It’s kind of an either/or proposition: you’re either on the river or you’re not. What you can do is make note of landmarks as they float by, in doing so participate in a similar kind of spiritual contemplation to Matthew Paris. Except, instead of meditating on Medieval Latin Christendom, you’d be meditating on a newly reunified U.S.A. immediately after the Civil War.

However, because the map only has one roller, like a measuring tape, it would be pretty unwieldy to try to actually use as it’s intended. What happens when you get up into Wisconsin and the whole rest of the map has unrolled onto the floor? What are you supposed to do?

Can you imagine what Matthew Paris would have thought of all of us swiping through the #vanlife hashtag on our Instagram explore pages? We’re all taking our own imagined journeys every time we scroll through someone else’s travel photos.

This isn’t to trivialize what was a serious religious practice, but instead to recall to us how our behavior as humans, and what we want to use media to experience, is similar in fundamental ways across the centuries. It’s just that now we’re reckoning with more powerful tools and nuanced techniques to achieve those experiences than ever before.

CONCLUSION - ARE YOU FEELING IT?

Thinking about how we access information physically, even down to the way our hands hold our phones, can help us think critically about the way that information gets served to us and absorbed by us.

This whole newsletter has been leading up to my main point, which is that if anyone at Samsung had ever taken a book history class, they’d know that their new flippy-open touchscreen phone is never going to happen.

People have been trying to get the advantages of a scroll into codex form for centuries, which makes the smartphone, frankly a miracle.

It’s tablet that can scroll and stay portable, PLUS it’s got things like hyperlinks which are a kind of text-navigating technology that would have made our ancestors’ eyes water.

(Except hyperlinks break immediately, because the internet moves so fast. I mean, these newsletters won’t even be useful in a year or two because half of these links won’t be viable anymore. Get ‘em while they’re hot.)

There’s an advantage to having handheld books that fold, and that advantage doesn’t hold up when the pages become digital signals on a handheld screen.

Still, digitized scrolls like the Canterbury Roll or the Chronique Anonyme are bound by the convention of the page, for better or worse. We can’t make a bespoke digital scroll-o-rama for every physical scroll, because it’s very expensive and extremely time-consuming. We’re going to squish them into the codex model and call it a day.

But the goals of the digitized scroll and the physical scroll are different, and that’s inherent in their incompatible formats. You have to be able to refer to a specific part of a digital object if you want to use it for research - we need our digitized scrolls to be able to do more than just scroll.

You also have to reckon with the fact that a digital object is bound by the rules of whatever media it’s displayed in, whether it’s a Mirador viewer or your TikTok For You Page. It’s worth thinking about the benefits and disadvantages of the conventions we slip into as we digitize, from the pages of the Book of Esther to the rigid narrative of the NYTimes digital “exhibit.” What is the format for? What goal is it serving?

Not to get too meta on you, but that’s kind of the point of this newsletter, too. That’s right, You’ve Been In A Scroll This Whole Time. As much as I want this newsletter to mimic an exhibit, which, in physical space, allows you to wander through it however you want, I’m still leading you through an argument and serving up examples. Even in the privacy of our inboxes, gestures teach us how to use the tool.

TUNE IN SEPTEMBER 1 FOR… BUILDING THE CABINET OF CURIOSITIES

For more on this, see Peter Stallybrass, “Books and Scrolls: Navigating the Bible” in Books and Readers in Early Modern England: Material Studies. Jennifer Anderson and Elizabeth Sauer, eds., Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002, 42-79.

For more on this, see Daniel K. Connolly, “Imagined Pilgrimage in the Itinerary Maps of Matthew Paris”. The Art Bulletin Dec. 1, 1999, vol. 81, number 4.

Another fab read! Love the way you communicate. I already know all this but you make it interesting all over again. Keep going!!!