Super Secret Symbol Club

"What good is a book if it doesn't have any pictures or conversations?"

I’m sitting here writing this to you in the lull between latke-making and dressing the large fake tree I’ve just brought out of storage that’s currently staring at me from across the room like a fancy Downton Abbey-era character waiting impatiently for his valet to dress him for dinner.

As it’s the holiday season, I’d just like to wish you all a happy and healthy new year, and to thank you so much for reading (especially those of you who’ve shared this newsletter with friends, enemies, families, lovers, pets, etc.) It means the world to me.

I’m looking forward to 2022, wherein things here at Rare Commons Industries Inc. will be getting funnier, deeper, weirder (if that were possible) and hopefully less sporadic. I appreciate you all for sticking with me, and if this is your first time reading, welcome!

1. VISUAL STORYTELLING AND WHAT NOT

Anyone else feel like we might as well all be on the back of a giant crayfish right now? That seems as plausible as anything else that’s happening at the moment. Would it help if you knew that crayfish walk forward slowly, but swim backward quickly using their killer abs, like so?

Basically, two steps forward, one step back. Sounds familiar, right? So goes the world. Which, not coincidentally, is a rough translation of the above emblem.

What’s an emblem, you ask?

Well, here’s another one:

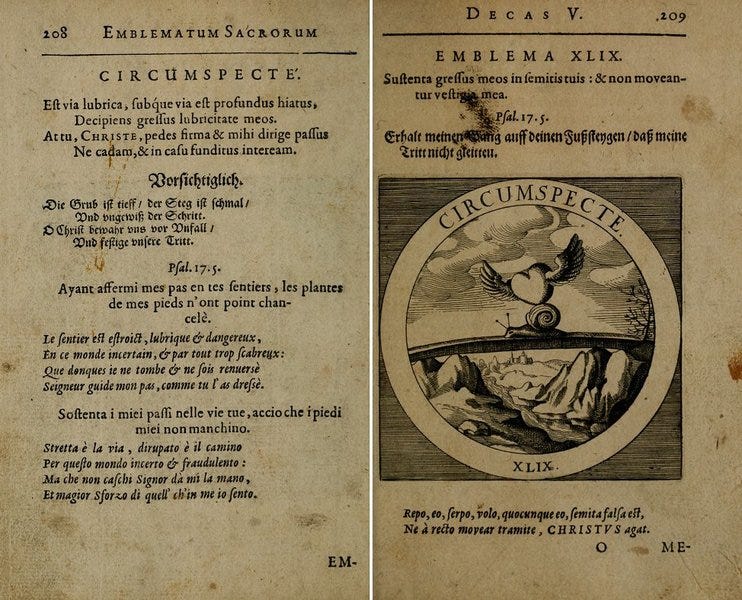

Emblem books are one of those rare-book topics that seems genuinely incomprehensible to most people outside the field, and probably many people within it, too (including me, until very recently). I mean, commonplace books were kind of a big swing, but this? This is a snail going hiking with a flying heart for a backpack, and… a poem? In three languages?

When I think of the word “emblem”, I think of its modern usage: a visible symbol of an idea. And that idea is usually either a commercial product or a country, so it’s basically an archaic term for a logo. Or, think of the heraldic shields that medieval people would have over their fireplaces, or whatever. Something’s always an “emblem” of something else - they don’t really stand alone.

But if you look at that snail, it’s clear that early modern emblems aren’t either of those things.

It’s not like that’s a particularly weird example, either. Here’s a hat volcano:

So why was the emblem book one of Europe’s most popular genres for a full 200 years? You think comic book movies are bad? Imagine these bad boys filling the bestseller lists for 8 generations.

And before anyone gets smart about it, it’s not because old-timey people were nuts. It was not lead poisoning, or the dancing sickness, or too much mead, or because they thought the world was flat (they didn’t). It’s worth thinking about people in history as people — not the same as us, but not so different, either, and not doing wild and wacky things without cause.

Why on earth would they bother to engrave a series of seemingly incomprehensible images, caption them, usually in Latin, and then write a little poem or essay about it after? And then, actually bother to pay money to print and read that? It’s not so their 9-times-great-grandchildren could make fun of them on the Internet because we assume we’re so much smarter and more sophisticated and better-smelling.

So what are emblems, and why do we care? Let’s take a closer look.

2. ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS

This world-lady hosting her weekly breastfeeding club with her animal besties seems to be having a good time, but what’s really happening on the page?

There are three distinct parts: on top, a phrase, “Nutrix ejus terra est.” In the middle, a rad picture that I hope to paint on the side of a van one day. And at the bottom, an epigram in the form of a poem.

Emblems were standalone combinations of words and images that were designed to illustrate an abstract concept. Riveting, I know. It might be easier to understand if I just show you. So I am going to try to make an emblem from scratch.

We start with a proverb:

ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS

We all know what that means, right? You can talk all you want, but until you do something concrete, it won’t matter.

And here’s a visual illustration of that idea:

For those unfamiliar, on the left we have Taylor Armstrong and Kyle Richards, two cast members of the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, in a dinnertime altercation. On the right, we have Smudge the cat, who does not like green vegetables.

Together, they create one of the most popular memes of the last few years, used to illustrate various arguments, mostly people’s outsized reactions to things that others don’t find to be such a big deal.

In the context of my made-up emblem, for all Taylor’s shouting, Smudge is still going to remain unmoved, because Smudge is a cat who cannot A. speak human language or B. be induced to eat anything he does not want to. His action (or lack thereof) is more powerful than Taylor’s yelling. Actions (Smudge) speak louder than words (Taylor).

So, the emblem:

Words, in the moment they're spoken, A particular power betoken. But, though fiercely spat, Without actions, fall flat And your enemy's peace stays unbroken.

Yes, I wrote a limerick for you. You’re welcome. It’s excellent, I know. (NB: Emblems never used limericks, perhaps because they hadn’t been invented yet. It’s just my preferred poetic format.)

Notice that Taylor isn’t the presumed speaker (yeller?) of the proverb “Actions speak louder than words.” She’s not yelling that exact phrase at the cat (although that would be hilarious). Instead, the proverb describes the scene as a whole.

And, the proverb isn’t something like “curiosity killed the cat”, because what matters isn’t that there’s a cat there, but that the cat symbolizes cold indifference and the refusal to be moved by empty words. It’s not about Smudge, it’s about his vibe.

The proverb or phrase is a concise explanation of an abstract idea. The image helps you conceptualize and remember the proverb, and the epigram is there to add context and further explanation to the picture. Boom. Emblem.

So, above, the hat volcano is reminding us that our all of our worldly glories (read: fancy hats) will sooner or later pass away like so much smoke.

The snail with the heart backpack is reminding us to tread carefully and stick to the right path, because we all wear our hearts on our shells more than we realize, and the world is a dangerous place. (I mean, the actual translation is more religious than that, but I’m paraphrasing.)

And, of course, the crayfish with the world on its back reminds us that progress isn’t linear. It all makes sense once you understand the symbolism.

And the breastfeeding world-lady? The translation of her proverb is “the Earth is his nurse”. (Whose nurse?)

Here’s a translation of the epigram:

This is obviously a fine translation of an elegant poem and NOT something a creepy guy would whisper to you on a crowded subway car. Breastfeeding was definitely a best-selling book topic across 16th-century Europe. Good translating, everybody. Mission accomplished.

…Okay, but seriously? This is where it gets interesting.

3. STEGANOGRAPHY

Emblems aren’t just cool pictures. They could also be used to convey sophisticated practical and arcane knowledge. World-lady comes from one of the cooler digital projects I’ve come across so far, Furnace and Fugue, published by the University of Virginia Press. It’s a born-digital version of Michael Maier’s 1618 edition of Atalanta fugiens (Atalanta Fleeing), which is an alchemical, musical emblem book in German and Latin based on the myth of Atalanta.

Classics nerds (and children who grew up watching Free to Be You & Me) will recognize the myth of Atalanta as the one where a cool runner lady refuses to marry anyone who can’t beat her in a footrace. Hippomenes, one of her suitors, uses 3 golden apples given to him by Aphrodite to distract Atalanta, and beats her to win her hand in marriage. Then they have sex and get turned into lions by Zeus. Just your classic rom-com, basically.

Atalanta fugiens takes this myth and infuses it with a structurally worrisome amount of additional meanings. There are fifty allegorical emblems, each accompanied by a musical fugue sung by 3 voices: Atalanta, Hippomenes, and the Apple. (If you want to learn more about how this works, I encourage you to explore the website, and especially read the introductory essay by Donna Bilak.)

The emblems are allegorical, and those allegories also describe alchemical processes, ingredients, and combinations. The harmonies and dissonances created by the three singing voices also echo the information given in the image and epigram. And it’s in Latin AND German.

So could you or I technically “read” this book? Sure, probably. The pictures are fun, and in the digital version you can listen to and follow along with the voices actually singing the fugues, which is nice. The whole thing makes me feel like a monkey who stole a smartphone. It sure does have some pretty pictures and make some fun sounds. But can I use it to, say, order a pizza for me and my gibbon friends? Absolutely not.

In order to fully read this book and extract all of the information within it, you’d need to have a background in Classical literature, music theory, alchemy, chemistry, Latin, mathematics, German, and then apparently there’s an entirely different book revealing the “secrets of nature” that’s hidden within the text, images, and music, so add code-breaking and symbology on to all of that. It’s all very National Treasure.

And that’s why they needed a team of five million academics to produce this digital edition: academia is no longer designed to produce people with the depth and breadth of knowledge you’d need to read, much less produce, this book. We’ve devolved into various disciplines that get separated at an earlier and earlier age: you’re a STEM person or a humanities person, a literature person or a history person, a modernist or a medievalist, and so on and so forth. And I’m not saying that’s a bad thing, but it’s part of why emblems are so incomprehensible to modern eyes.

I decided to write about emblem books because when I was in grad school at the University of Illinois I found out they existed, but I did not find out why they existed, or why U of I would bother amassing one of the biggest (and best) collections in the world. (Sorry not sorry, I’m going to talk about library school in every issue of this newsletter.)

I understood why people in rare books care about bibles and antiphonals and books of hours—religion and religious rituals are compelling and moving, the books are usually really expensive and fancy, etc. I understood why people care about Great Literature like Shakespeare and Chaucer, because I, too, have English majors in my family. But emblems? We don’t even talk about them anymore, much less produce them. There’s no current cultural context for them.

…Or is there?

4. NO _______ ALLOWED

Everyone, I want to introduce you to my good friend, Memes:

We all get it, right? The girl in red doesn’t have to be the symbolic personification of Desire or Persephone or Lead for us to understand what’s going on here.

Here’s another one:

Okay, after this one I’m done. I promise.

Basically, memes are combinations of images and text that, because of the Internet, have become widely reproducible and applicable to a variety of situations. Different image templates get overwritten with new text in that alluring cocktail of Internet virality: humor, novelty, and relatability. In my definition, memes describe situations from a third-person perspective, rather than reaction images which are first-person stand-ins for the poster’s emotional state.

It’s about communicating meaning through several vectors at once, synthesizing a bunch of information to convey ideas, feelings, and moods at warp speed.

As someone who grew up listening to the dial-up tone logging onto AOL, who learned to type because of AIM rather than Mavis Beacon, who stayed up until 4am with her friends watching flash animations of dancing badgers and imitating Strongbad, I know that memes are dumb. They’re not for real, serious people.

Except, somehow, everyone knows what Pepe the Frog is now, because we have to, for politics reasons. And our parents are using emojis, and somehow 8chan is getting coverage on CNN, and all of the weird stuff you used to do on the family desktop at 2 in the morning is now mainstream, and your Aunt Jan is posting QAnon memes to her Instagram stories. That’s where we are.

Francis Bacon, writing in The Advancement of Learning (1605), describes the purpose of emblems like this:

‘Embleme deduceth conceptions intellectually to images sensible, and that which is sensible more forcibly strikes the memory, and is more easily imprinted than that which is intellectual.’

(Sensible is used here to mean “emotional”.)

Feelings are stickier than facts. If we’ve learned anything over the last 2 (6? 10? 20?) years, it should be that. The stuff we don’t take seriously can be extra-powerful because it slips into culture under our notice, on the level of feelings and jokes. Just because it’s humorous doesn’t mean it’s not serious - and self-consciously ‘serious’ stuff always gets more scrutiny. Jokes are jokes, right? Can’t you take a joke?

Memes are the shorthands that make up our Internet culture, which is really a vast universe of subcultures. Now that so many people are on the Internet, memes are more useful than ever in determining the in-group/out-group dynamics of any given group of like-minded people.

Memes can be just as incomprehensible as emblems if you don’t ‘get’ the joke. And that’s kind of the point.

Both memes and emblems are about the allure of the puzzle. The interactions between characters in each image reveal layers of meaning, making memes and emblems both puzzles to solve and tools for emotionally reinforcing a particular argument.

Ever put your pet’s food in a puzzle toy as a treat? That’s essentially what we’re talking about here.

There is a meaningful difference between symbolism we’re all expected to understand, and symbolism we’re challenged to decode. The latter earns us a place in a select group of those in-the-know. If you want an object lesson in how addictive puzzles can be, just look at QAnon. If you don’t have the right cultural or informational background, you’re clearly not part of “our” secret club, so you can take your toys and go home.

Memes and emblems are both image puzzles. So, are emblems essentially just early modern memes?

5. NO

I mean, obviously not.

If information density were measured using chocolate content, a meme would be a Tootsie Roll, and Atalanta fugiens a box of dark chocolate truffles. There’s just no comparison.

It’s not enough to think of emblems as frivolous, entertaining puzzle-boxes used to capture a particular feeling or remind people of a favorite proverb. Memes are secretly powerful, but making memes is free. Printing emblems was decidedly not.

In her 2007 article “Early Modern Emblem Books as Memorial Sites”, Tamara A. Goeglein argues that emblem books functioned as memory aids to help their readers argue and lecture on the spot. By fixing a series of emblems in various rooms of their ‘mind-palace’, an early modern thinker could remember the entirety of a 3-hour lecture by heart. Essentially, emblems were mnemonic devices.1

In the early modern period in Europe, oral/aural culture was in the process of being overtaken by the printed word. If you’ll cast your minds back to the first Rare Commons newsletter, you’ll remember that parchment was all Europeans had to write on for a significant chunk of history. With the advent of paper, writing got less expensive and printing became possible, and then inescapable.

So, if you were a scholar, previously you would have had to use complex memory techniques to remember your professors’ lectures, and used them again to compose and recite your own arguments. Emblem books, according to Goeglein, are the printed manifestation of this practice.

And that leads us to an interesting paradox, because when you can print, suddenly you can make things like encyclopedias, dictionaries, thesauruses. Emblem books are reference works for a scholarly tool, memorization by rote, that books themselves would help make obsolete. So when Francis Bacon talks about using images to create emotions in order to remember concepts, it has quite a practical application.

The creation of printed reference works meant that information could be more easily categorized, dissected, differentiated into separate disciplines. And so a book like Atalanta fugiens goes from being a masterwork, to a curiosity. Atalanta wouldn’t have been used as a mnemonic device, but the emblems it contains represent a way of organizing and conceptualizing knowledge that lost relevance as cheaper printed books gained traction.

It’s been my practice in writing this newsletter to try to show how old books — seemingly irrelevant to modern culture — connect to or anticipate ways we use media every day. But sometimes it’s just as important to understand how they’re unique to their own times.

It would be simple enough to say that people have always used images in their storytelling. But comparing emblems to memes reveals the mechanisms by which visual storytelling works, and the power it has to create our social worlds and dictate the limits of our imaginations.

STAY TUNED FOR MORE RARE COMMONS, COMING NEXT YEAR.

Tamara A. Goeglein. “Early Modern Emblems Books as Memorial Sites.” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 69, no. 1 (2007): 43–70. https://doi.org/10.25290/prinunivlibrchro.69.1.0043.

Interested in learning more about emblems? Check out the Society for Emblem Studies’ digital resources page: https://www.emblemstudies.org/digitisation-projects/. The University of Oregon has a great introductory blog post, too: https://blogs.uoregon.edu/scua/2020/08/24/emblem-book-collection/